A few months ago, I received a letter from Mr. Cason which included the cover of a book. The picture on the cover was of a landing craft on D-Day.

Marked in red ink was an X in the centre. On the back of the cover, Mr. Cason had written:

"Liberty, my position was on the front of the landing craft (where someone is standing). This was not the landing craft I was on, but this is what it looks like. There was/is a ramp chain (out of sight) that part of my right boot caught and almost cost me my life. It eventually broke with tremendous effort. We were weighed down with about 80 lbs of equipment (40 lb mortar piece, ammunition belts (2), 4 8lb mortar rounds) and weighed down, of course, with water up to my chest (also a steel helmet and combat boots that were water-logged). "

After finally disengaging himself from the dangerous chain, he slogged forward to the beach. In one of the ludicrous moments that happens during times of intense pressure, Mr. Cason yelled out, “A guy could get killed out here!” It was an absurd statement, but as he explained to us, “In training they used real bullets, but never with the intention to harm. Suddenly, people were trying to kill us, and it was the first thing that popped into my head.”

The weather was terrible,” he wrote, “as you probably know. BUT I made it though and now for combat on the beach and beyond. Whoopee? Not really! The whoopee part."

Mr. Cason’s war continued: fighting the Germans, battling the cold, liberating a Nazi concentration camp. There were moments of great sadness -- when he returned from hospital to find his best friend killed; and moments of great joy and happiness -- when Victory in Europe was declared. He was eventually sent home and took with him many medals including 2 Bronze stars, 2 Purple Hearts, and the ETO Campaign medal with 5 battle stars. He remained on active duty in the army for 22 years and was proud of his service to his country. However, with all his medals and glory, there was one deed in his life which he considered “the most compassionate thing I ever did in my life.”

“I lost my best friend during WWII. He was killed in action on or about July 10, 1944, in Normandy, France. I was in the hospital in England at the time and didn’t know he died until I rejoined my unit... He had a daughter, Sue... She was about 3 years old when her father, Raymond, was drafted in the army and she never saw him again. For 60 long years, Sue tried to find out what happened to him or if anyone knew him. I responded to a notice in an army (military) magazine that had her name... and called her right away. When she answered the phone, I told her who I was and that I was a good friend of her dad. I identified his physical features such as height, weight, color of hair, and a slight gap between his two front teeth. She let out a yell and told her granddaughter, who was nearby, that there is someone on the phone who knew him. After 60 long years she finally found someone who knew him. Liberty, I am telling you this because from the bottom of my heart it was (still is) one of the most compassionate things I ever did in my life.”

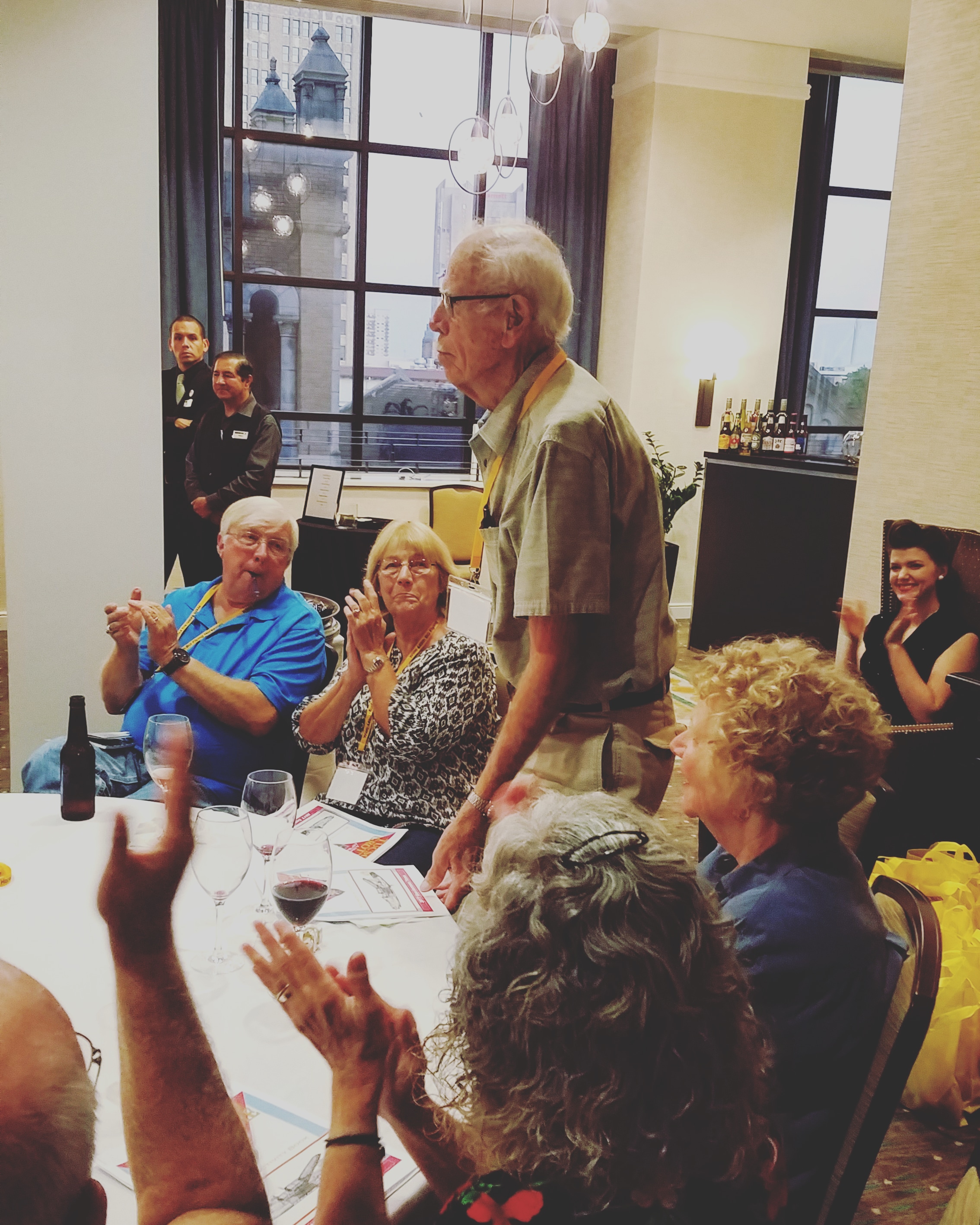

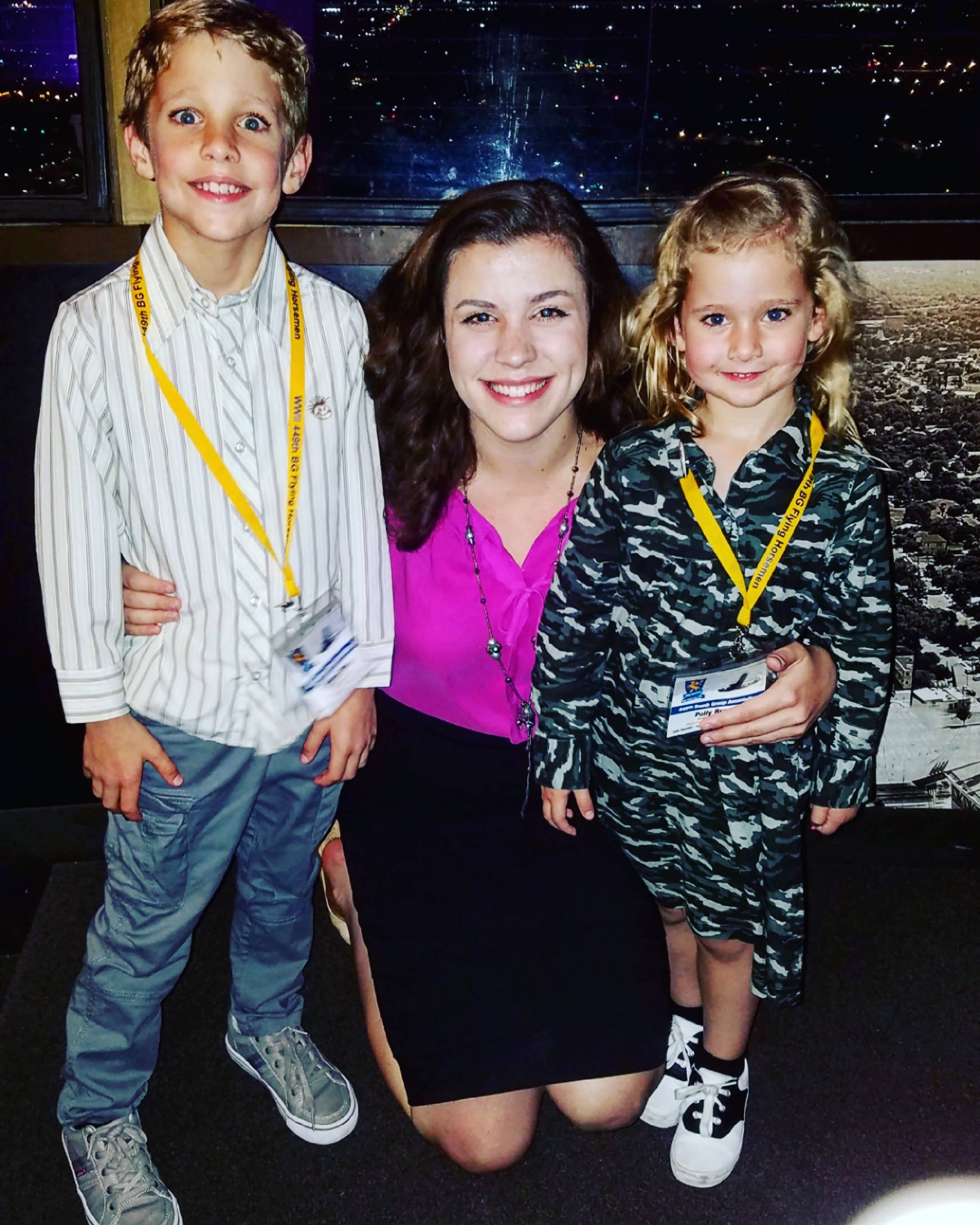

My family and a very close friend met Mr. Cason last fall and just fell in love with this dear man. He delighted everyone with his harmonica playing (simply the best), and he told us stories of his war which were unlike any we had heard in description, detail, and even sound effect. A few weeks ago, my family and I were very heavy hearted to learn that this dear and precious man had passed into eternity. It came somewhat as a surprise to us, for no matter how frail he was, the life and vitality in him seemed unbounded. The friendship my family and my dear friend had with Mr. Cason could be considered somewhat unusual as we met him but once, and after that our only communication was through letters. But it was a beautiful friendship that sprung out of an unlikely conversation on a blustery day.

The history that Mr. Cason held from his experiences was rich. It is terribly sad to realize that now we have only memories and the letters he left behind. Sometimes people ask us why we want to do what we do. Even the dear veterans ask. The answer is really summed up in the life story of Mr. Cason, a life so full and rich, committed to county, replete with duty and sacrifice, that we feel an obligation to know and tell his story. He worried that the young people today would not know what men like him went through. It troubled him that many “high school kids have never heard of D-Day or the Battle of the Bulge.”

And there are so many more men like Mr. Cason out there. Lives full and rich, but whose stories will never be told because they are living out their last years quietly at home or in care facilities. We want to make sure that men like him are not forgotten. Their stories are so important for us to hear and remember. Not just for the stories’ sake, but because from them we learn more than we could ever learn from any textbook. There is a quote regarding this that I have read hundreds of times:

"The march of Providence is so slow, and our desires so impatient; the work of progress is so immense and our means of aiding it so feeble; the life of humanity is so long, that of the individual so brief, that we often see only the ebb of the advancing wave and are thus discouraged. It is history that teaches us to hope." - General Robert E. Lee

I began by telling the story of one of thousands of American boys who landed in Normandy in June, 1944. One of thousands. It is easy to forget when reading history books that the massive numbers recorded are made up of individual human beings; each with a unique story, an entire life and soul. But it is true. And that day on Utah Beach, Mr. Cason was just one of the thousands, without a name as far as the Commander in Chief knew. But to us, he is now an individual with a story, representing all the other boys of Utah Beach and what they endured. His story and his life will never be forgotten.