"My War" as Told Through the Art and Letters of Tracy Sugarman

/When you are a child, the first rule of picking out a book is, “does it have good pictures?" If the answer is yes, then you open the book and read it. It the answer is no, you put the book back on its shelf. Why read a book with no illustrations?

Then life catches up on you, you grow up and and have to realize that books aren’t all about pictures. Before you know it, all of your “adult” books just have words in them - long, sophisticated words that little children wouldn’t dream of knowing. And if they could, they would dismiss them as nightmares.

That’s pretty much what happened to me. My shelves (though I love each and every one in them), are nonetheless filled with picture-less books with words starting at 5 syllables each. They are long, sometimes dry, and full of lots of and lots of information. I read them and enjoy. I don’t think about the fact that they are picture-less.

However, once in a blue moon - when the unicorns and werewolves come out and play together- the 6 year old in me pops up and demands that I find books with good pictures in them.

That’s how I stumbled on this particular book, My War by Tracy Sugarman.

“disaster in the channel”

About a two years ago, I was visiting my brother in Florida and happened to stop by the Sanford renowned book shop, “Maya Books and Music.” It was completely charming, and I would have been happy walking away with half the store. But since my pocketbook groaned and declared otherwise, I decided I would have to be satisfied with this little find.

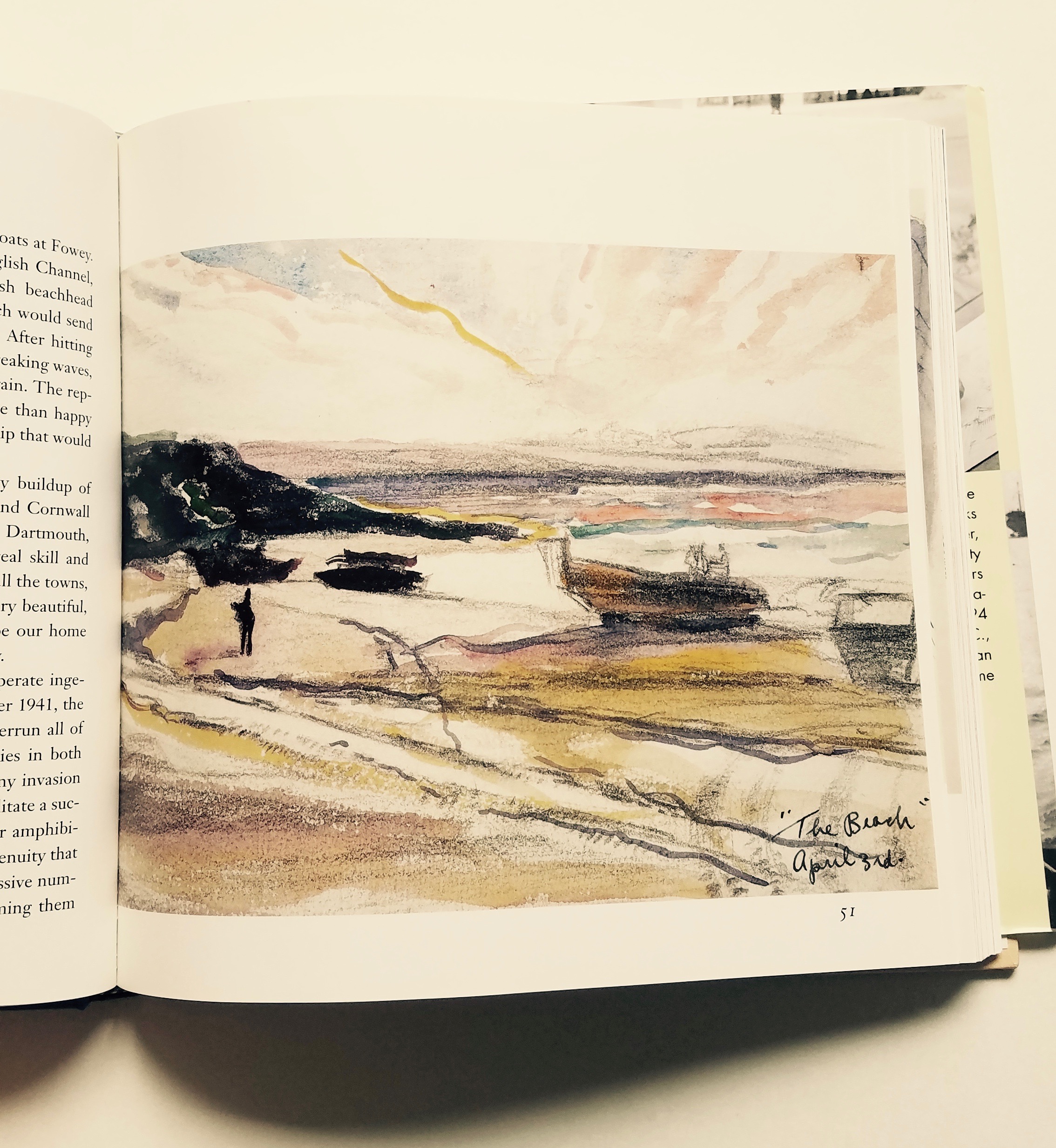

The moment I opened its cover, I was struck by the gorgeous watercolors and sketched images liberally distributed throughout the pages: simple pencil portraits of servicemen the author had encountered, dramatic scenes from a storm in the English channel, friend Tommy doing laundry near a windowsill of daffodils.

“Tommy and his laundry, with daffodils”

Alongside these images were detailed letters to his wife, "darling Junie," narrating his life as a young ensign in the US Navy the months surrounding the greatest naval invasion in history, "D-Day," and interspersed with his retrospective commentary years later when he would publish his drawings and letters.

The impetus for “My War” came from a parting gift Sugarman’s wife, June, gave him as he was preparing to go overseas in January, 1944.

“It’s a little something for both us us.”

I edged open the package and peered inside. Sketch pads! And pens and a tin of watercolors!

“How wonderful! You’re too much, Junie. But those are for me. "What’s for you?”

… Very quietly she said, “For me, it’s your sanity. And maybe some pictures so that I’ll know you’re alive and kicking! Hold on real tight, darling. You’ll be back and I’ll be waiting.”

“Junie” did wait, and hundreds of letters later, thousands of miles traveled, a great Naval Invasion, and a World War, Sugarman came home. At end of the book, Sugarman regrets that he was not able to save all the “funny, wonderful, life-sustaining letters” he received from his wife the months and months he was away. “They were read and reread, folded and unfolded until tattered, and finally abandoned when the next sea-soiled envelope arrived.” But thanks to Junie’s care, his did, giving us this thought-provoking and informative narration.

Tracy and his wife june “a summer day at ocean view”

In his preface, Sugarman says,

“I leave it to the historians to chronicle the strategies and dynamics of the global conflict of World War II. With the perspective gained from more than half a century of scholarship, they delineate the battle lines and campaigns, the tactics and struggles of the world I inherited after Pearl Harbor. They know a great deal about “the war”. But they didn’t live my war.

It is my conviction that ever sailor and soldier in World War II fought his own war. It was a struggle that only sometimes permitted him to see the enemy. But as he stared into the darkness from his ship or beachhead, he very soon began to see himself. So new to manhood, he watched himself grow through fear and loneliness, boredom and exaltation. It was an inescapable odyssey for each of us who served.”

And such an odyssey he paints! Beautiful and haunting at times:

“There are those long twilights here now. The sky is billions of miles away, and you feel very much alone. The water stretches away forever -no waves, hardly a ripple. The ships sit alone in the water, each in its own pool of aloneness. The sky arcs up from millions of empty miles beyond the shore. And straight up there’s nothing. It’s big and empty and very quiet. The sun goes away, and it’s still too big, too light. The emptiness comes off the water and crawls right into you.” (July 1 - T. B.Robertson)

At other times, he writes the raw and truthful: realities of the high price war takes on youth and innocence:

The inconsistency between the American fighter and the American sailor or soldier is staggering. I remember so well how inadequate I felt when I tried to tell you how wonderful those guys were on the beaches last June. I wouldn’t take back a word of it. I feel now as I did then, but coupled with it goes a feeling of wonder. Wonder as to how such marvelous fighters can be such rotten people… Their conceit, their arrogance, their obscenity and vulgarity in front of anyone shames the life out of me… They never apologize for our own shortcomings, and get a majestic sort of pleasure in making the English painfully aware of theirs. In every conversation the “biggest,” the “newest,” the “cleanest,” the “fastest,” the most and the best of the good, the least of the bad… Individually, I would do anything for any of them. But as a group they are the antithesis of anything I desire. I don’t want to close our eyes and pretend the bad and the wrong and the ignorant aren’t there, darling. Those things are real, and too important to both of us. I want only to reject their standards and their values. They revolt and shock me. (Feb 23, 1945)

In his retrospective commentary, Sugarman adds some thoughts to the harsh words he spoke about the American Serviceman back in 1945:

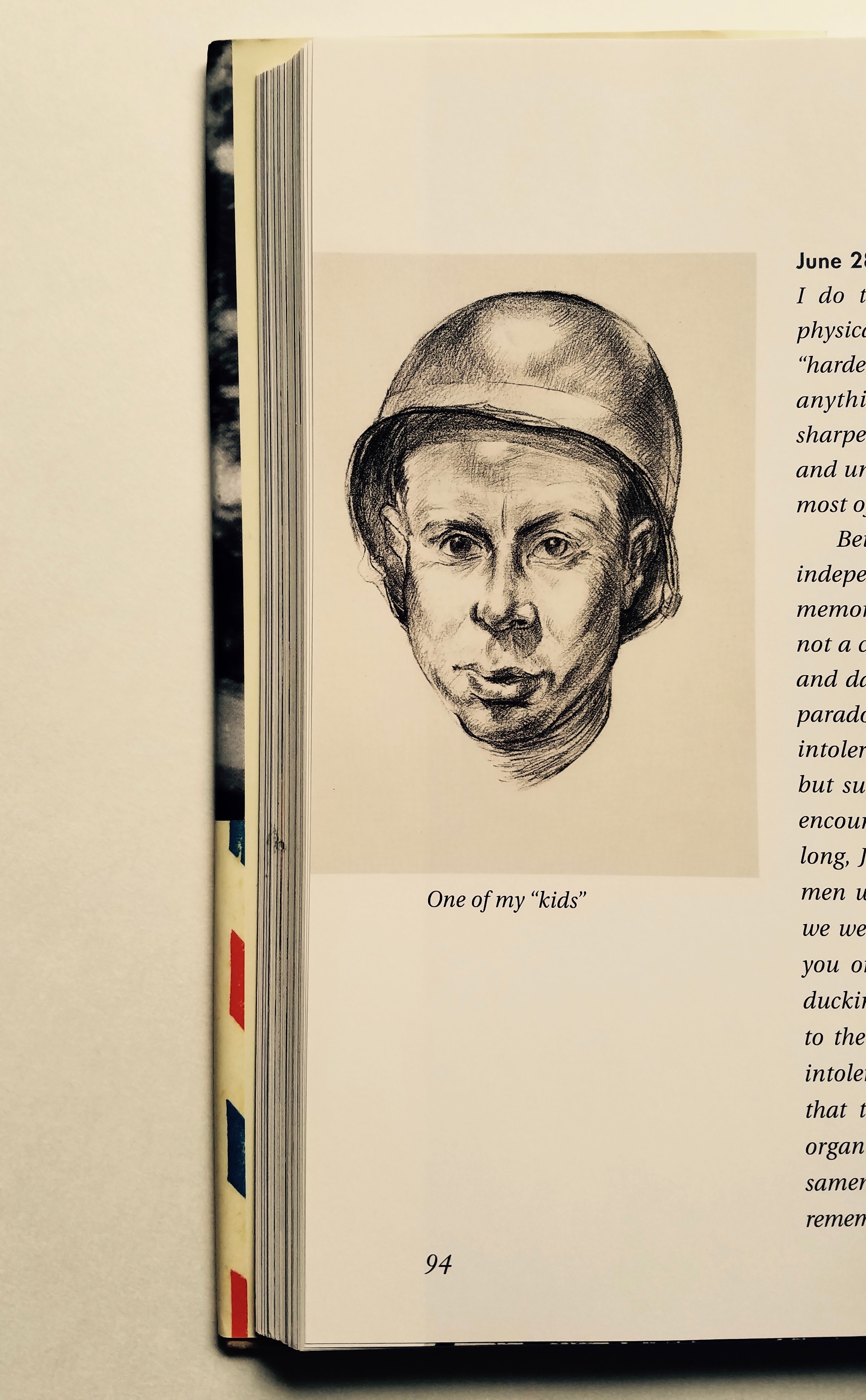

One of my “kids”

There are unexpected surprises that one finds when unearthing an intimate record from one’s youth. The most astonishing to me are those letters from the war that describe my perceptions of many of the men with whom I served. They swing from admiration to revulsion, from pride to anger, from pleasure in their company to embarrassment at their provincialism and lack of sensitivity, yet older is not wiser… It is hard to remember how young we all were when we went of to war in 1944. Most of the sailors on my ships really were the “kids” I wrote of in my letter to June. Put to the test of physical courage, they were remarkable, often accomplishing the seemingly impossible and usually with pride and good humor. When off on liberty or leave in a war-torn England, however, their ignorance and immaturity often displayed itself in ways that were embarrassing to their fellow servicemen and arrogantly hostile to our hosts.

For the most part, these were kids who had never been away from home, who were fearful and tried to cover it with bravado, who had little or no sense of history, and often showed that they resented being there. American education had ill prepared them to understand how uniquely fortunate their own country was due to geography, not because we were born to be “number one in everything.” Nor did most of them understand how indebted we were to those who fought alone for so many years, although the shattered homes and churches and towns around them bore the dreadful testimony to the high price that the English had paid for all our freedom. For too many of the Americans, this war was not really our war. It was their war, “and if it wasn’t for us Yanks, they’d sure as hell lose it.” Thankfully, as a nation, we are a long way from the provincialism that was so rampant in many Americans in World War Two. -Sugarman

But even though he had hard words to say about the things he saw, he never once took for granted the sacrifice these boys were making.

“Young men dying seems to me, somehow, the greatest tragedy. The acceptance of death has been something new to me. And I know that death serves only to accentuate the love of living we both share so dearly. The bridge between is so complete, so final that you finally stop thinking of its terrible proximity and cling rather to pulsating life. Your laughter is a little quicker, your thinking is a little less shallow, your energies and ambitions fired with a new urgency.” (August 17)

For our heart’s sake, not all his letters dwell on the hardships and seriousness of the job he and millions of the boys were experiencing… there are plenty of carefree and amusing accounts, including one which makes you marvel at the serendipitous happenings that sometimes occur in war:

“I had been napping, riding out the foul weather that had stopped all our work off the Robertson, when Mike, the stewards’ mate, excitedly came in my room and shook my shoulder. “Mr. Sweetenin’! Wake up! There’s a Lieutenant Sugarman looking for an Ensign Sugarman. Is you he?” I stared at the grinning sailor and bolted out of bed and raced up to Operations. The signalman pointed to the LST lying off our bow. "Signal came from there, sir.”

I stared across the water at the ship, rolling wildly in the windy chop of the Channel. Marvin here? It was too impossible to believe. But how marvelous if it were so! My older brother had been my role model in so many ways, and I had been the best man at his wedding. But I hadn’t seen him now in over a year. When I was getting my commission at Notre Dame, Marv and his wife, Roni, were stationed in Alabama… In my last letter from the folks, they were rejoicing that Roni was expecting a baby, their first grandchild. But not a word that Marvin might be shipping out to Europe. And now a few hundred yards away, he was coming to Utah Beach! I could just imagine the folks’ faces when they got the news!"

In his letter to Junie, he related their first “meeting.”

The weather got more and more wild, and there was no way of getting there. So tonight I called their ship by radio and summoned Marv to the radio! Although strictly against regulation, it was too great a temptation. And honey, he sounded so wonderful! The magic of a familiar voice from home is something so good it can’t be described. Imagine, angel, having Marv right here on my beach! … The conversation was pretty crazy, both of us were so damn excited.

[Sugarman] “Hey, I understand you’re gonna be a father! Over.”

[Marv] “You’re yelling me! Over.”

[Sugarman] "I didn’t think you had it in you. Over.”

[Marv] “Are you kidding! Over.”

[Sugarman] I think it’s wonderful! You got a bottle of Scotch? Over.”

[Marv] “Lots of it. Get the hell over here! Over.”

It’s easy to see in their delighted faces the most happy surprise of being reunited with a bit of home on the beachheads of Normandy.

Another time, he relates an amusing incident that happened shortly before he was shipped overseas to England:

“Late in January 1944, orders came directing our whole outfit to move out. We had all trained exhaustively and were eager to get to the English staging areas…. As we were packing to leave the base, unsettling new orders arrived.”

Sugarman and two other Ensigns, Tommy Wolfe and “Andy” Anderson, were detached to train a new batch of sailors soon to be arriving. Flattered but disappointed, he resigned himself to the fact it’d be a few months more before going over. However 3 days later, they received new orders: “Three officers and thirty men were to proceed immediately to Long Beach, NY to await transport to the ETO.” There was just one hitch… their new crew turned out to be more in the style of the Dirty Dozen rather then the “ship, shape, and bristol fashion” ones they’d just said the adieus to.

Sugarman wasn’t so sure. He’d grown up in Syracuse, NY and the only “tough characters” he was used to were the ones he met on the Lacrosse field and shook hands with at the end of each match.

“I finally took my buddy and fellow ensign, Tommy Wolfe, aside. A tough, street-smart New York kid himself, Tommy looked and sounded like Jimmy Cagney. He grinned at my concern about our new crews. “Relax, Sug. This is the biggest break these characters could dream of. If we’re tough and fair with them, they’ll work out great. I grew up with guys like them.””

Just as Tommy said, it turned out to be okay. “But I wondered how, at twenty-two, I could make these men believe I was tough enough to take them to war.”

On the train north to New York, June rode with the released prisoners. At the first opportunity, I took her aside. “Are you okay? They giving you a hard time?” She laughed. “They’re kids,” she said. “They’re tough kids. I wouldn’t want to be the Germans when they hit the beach. But they’re really very sweet.” I stared at my wife. “Sweet?” “Well,” she said, grinning, “they’re very sweet to me.””

The book is rich and full. The layers of depth and insight that comes from a mere 23 year-old are striking and cause you to go back and re-read the thoughts he penned to his wife during the tempestuous 18 months he spent overseas. 18 months that changed his life and the lives of millions around the world.

I do think have left me unscathed physically and mentally. I do not feel “older thank my years” nor “hardened by the crucible of fire.” Nothing I’ve seen has changed anything fundamentally in me. Possibly my resolution has sharpened some, my enthusiasm slightly tempered, my tolerance and understanding somewhat broadened. I think that’s happened to most of us in some degrees. Being here, there has had to be an assertion of self and independent spirit. If these are bounded by humility and a decent memory of what actually was, then it should be a healthy influence, not corruption. -Tracy Sugarman

Thank you for the lessons, Mr. Sugarman. And thank you for the pictures.