Bob the Geordie: Driving for the British Army in Normandy

/Last weekend I was perusing old letters sent to me by my veteran friends years ago, back long before the girls and I ever started Operation Meatball. Some of them are short one-liners, others are lengthy multi page stories, all quite special to me. Since we could all use a good dose of positivity right now, I thought it would be fun to share some of the more lighthearted and cheery ones here over the next couple of weeks.

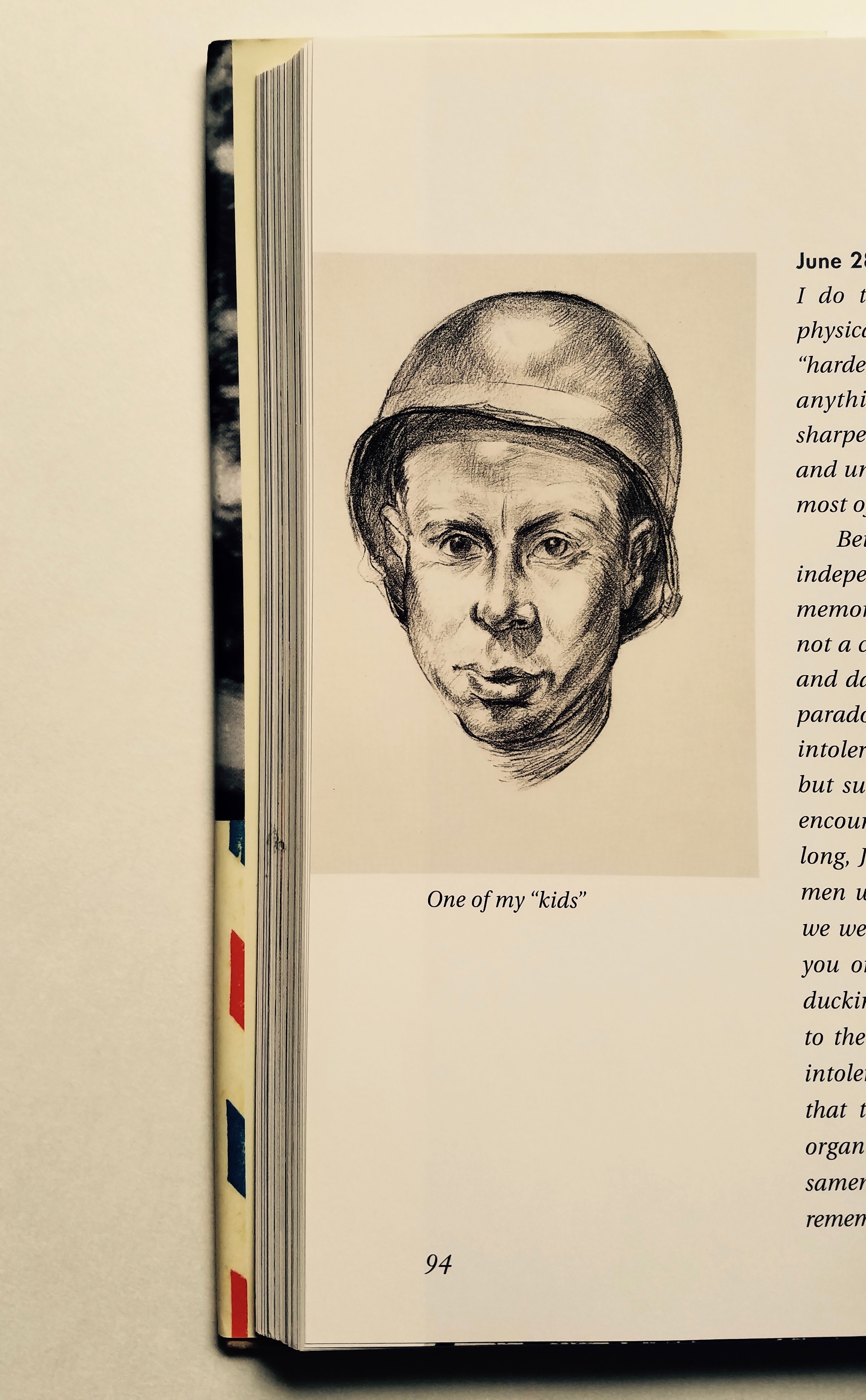

Picking out a first one to start the series was easy. In 2011, I met Englishman Bob Douglas, a character if ever there was one. One never quite knew what next was going to come out of Bob’s mouth, but whatever it was, you were pretty sure you wanted to be there to hear it. Bob also had that rare quality of being able to walk into a room of strangers and within minutes taken prisoner of everyone’s heart with his bright Geordie personality and riotous wit.

He passed away several years ago, shortly after his best mate died. They were inseparable, and their friendship is a story for another time. So without further ado, here is Bob's letter.

A Young “Bob” Douglas

July 19, 2011

Dear Liberty,

I must start this letter by saying that I was pleased to get your letter dated July 8th and that you and your family arrived home safe and well, also that my name is Bob. Please use it.

… At the moment I'm in fine fettle (Geordie slang for I'm in good health). I'll try to answer your questions as best as I van.

I was born January 13th 1925, my parents were like everyone else in New Gateshead (hard workers that scratched out a living). When I was 8 my mother died in childbirth with my youngest brother William, (oor Willy - more Geordie for "Our Willy"). I thought that I was 1 of 10, but later found out that I was 1 of 18, this is because both parents married twice. All of my life my brothers and sisters died. There is only Willy and myself left.

I was called up when I was 18 years old in 1943. Everyone had to do their duty back then, I done my training as a soldier then the Army found out that I was a driver in civilian life, so they made me a driver. Two weeks before we went to Normandy I was taken off driving duty for special training. When it was done I didn't go back to driving. I landed in Normandy on D-Day + 9 and was in the front line for a couple of weeks, when I was told to report for driving duty again. When my C.O. saw me he exclaimed, "Douglas! I thought you were dead." It turned out that the driver that took my place was called John Douglas and he had just been killed.

With Bob in Normandy in 2011

Yes I have lost a lot of friends in France, Belgium, Netherlands, and Germany. I was one of the lucky ones, I was wounded by a piece of shrapnel and then sent straight back to the front. I think that I was under the hand of God. I always hoped to see my family again when I was out there. A week after hostilities ceased my father died. I was given 2 weeks compassionate leave. By the time I got home, he had been buried a week. I met my future wife on this leave.

I went back to my Regiment (which was being disbanded at this time), I was put into the South Lancashire Regiment and sent to Palestine for two years. I corresponded with my wife to be. I returned home and married in 1947, we had a son (Robert) in 1948 and a daughter (Ann) in 1949.

Sincerely yours,

Bob