Return to the Black Sands of Iwo Jima pt.2

/First sight of Iwo Jima

“What does returning to Iwo Jima after 70 years mean to you?” I asked a 90 year old, soft-spoken Marine.

He started to tell me, then stopped. We were on the top of Mt. Suribachi overlooking the island of Iwo Jima. With his good arm, he had just pointed out to me the location of his landing beach and subsequent movements. At his side hung a limp prosthetic arm, a memento of the 12 days he had spent on the island.

“Give me a minute.” He said, his voice choking a little. He looked back over the island, trying to get control of the emotion in his throat. After a few moments of silence, he started to speak again, but his voice cracked. “I’m sorry. I can’t tell you. It’s too...” His hand instinctively went to his prosthesis.

“It’s okay.” I told him. Without saying a word, he had expressed everything.

- - - - - - -

The morning we departed for the island of Iwo Jima, we left our hotel on Guam at the unrighteous hour of 3 or so o’clock in the morning. Most the folks on the trip (self included) had only enjoyed 2 or 3 hours of sleep, but excitement and anticipation proved to be a good enough antidote. In the airport, we were joined by the rest of the crowd, all in all totaling about 450 people (3 planes' worth).

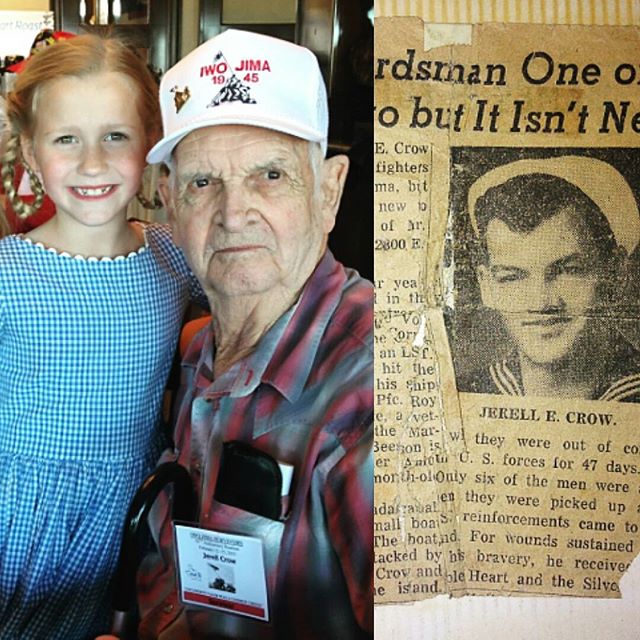

During the flight, I turned around to introduce myself to the two veterans behind me: Sam Weldon, 4th Division, a real brass-knuckles Marine; and Frank Pontisso, 5th Division, much more soft-spoken than his companion. They both came from way up north, their accents betrayed. For both of them, Iwo was their first and last combat. Mr. Weldon came off the island relatively unscathed, with the exception of almost complete loss of hearing. He ended up as an MP on Guam. Mr. Pontisso was less fortunate. On his 12th day, a mortar blast exploded near him and two of his buddies. All three survived, but his right arm was badly damaged. With it packed on ice, he was shipped off the island.

“Ladies and Gentlemen, in a few moments we will be approaching the island of Iwo Jima...” It was almost amusing to hear the Captain say this over the loud speaker. The usually dull, “Welcome to your destination,” was changed entirely by those two little words Iwo Jima.

The plane circled the island three times before landing, so that all who wanted could cram into a window seat and grab a shot of this historic island. The island was beautiful. Not in the way the Golden Gate Bridge is beautiful to a sailor who has been at sea for many months, or New York Harbor was to the immigrants in the early 1900s. But beautiful in the haunting sense of the stories it holds, the bravery and courage unequaled, and a history that must never be repeated.

I looked over at Mr. Pontisso in the seat behind me and couldn’t help but wonder what he was thinking. The last time he’d seen the island was the day he was hit by a mortar. Diving into a foxhole, a corpsman had given the wounded marine a shot of brandy before he passed out. The next thing he knew, he’d been taken off the island and hospitalized. Everything was going fine in his recovery, until gangrene set in. There was no choice but to amputate the arm. His war was over, and he was sent home with a Purple Heart.

Now, 70 year later, he was coming back. I snapped a quick picture. It is strange that a piece of lava in the middle of the ocean can hold so much significance to us.

- - - - - - -

Immediately after debarking, we headed up to Mt. Suribachi. From the top of Suribachi, we could view the entire expanse of the island; an impressive view, but not exactly the same view the flag-raisers had 70 years ago. Then, the surface of Iwo had been bombed to pieces and hardly a lick of foliage was to be seen on the island. Today, it is completely covered in greenery and can almost be considered lush.

This was a bit disconcerting to some of the vets who had been hoping to find familiar landmarks. Now covered up with shrubbery, it was like finding a needle in a haystack to get precise locations. One of them remarked to me, “We should just bomb it again. Then I’d be able to find my way around okay.”

On top of the mountain, an exciting chaos was ensuing. Veterans and friends crowded around the Marine Monument for a photo, or raised their flag on the pole briefly, all the while dodging news cameras and photographers. I had to gulp and hope it wouldn’t go away too fast.

Time did seem to halt a few times as I talked to a couple of the veterans coming back for the first time. They spoke slowly, carefully reflecting on their surroundings. One of them said that no matter how much you prepare to revisit the old sites, it still kind of hits you hard.

“I’ve been having nightmares for 70 years.” Sgt. J. Coltrane told me while we were sitting atop Suribachi. “I’m hoping that after this, I won’t have them any more.”

Standing up there, I remembered the story Colonel Bill Henderson had told my dad the first time he went to Iwo Jima in 2005. In his outfit was a young Marine who had earned the name “Buttermilk” due to his youth and inability to order anything stronger at a bar. The Colonel didn’t know him too well, being new to the unit, but he recognized him still. After landing on the first wave, Henderson (then a Lieutenant), was struggling to get his men together and up the beach. At one point, he looked over and saw Buttermilk standing in the sand with a dazed face. “Buttermilk!” He shouted out. “Get up and go. Don’t just stand there. Move it!” Knowing they had to keep moving forward quickly, he was surprised that the young Marine just stared blankly at him. Realization hit a moment later. The lower half of Buttermilk’s body had been blown completely off. Colonel Henderson later reflected, “He very slowly toppled over. At moments like that, there was little choice but to move on or die, paralyzed with fear, confusion, and anger.”

- - - - - - -

The ceremony on Iwo Jima was formal. The representatives from both America and Japan spoke, followed by a wreath laying. Each side paid tribute to the men who died; they spoke of forgiveness and healing, and the unity between our countries. It is always striking to me to see two countries that warred so viciously with each other, make peace, and then for the next dozens of years became strong allies.

Speaking of forgiveness, we had, with our Military Historical Tours group, a special guest: Mr. Tsuruji Akikusa, a Japanese Naval Radioman. Mr. Akikusa had aspired to be a fighter pilot, but his father, not wanting him to die, had him sent into the Japanese Navy. This would be a safer place for his son. But it wasn’t. Before long, 18 year old Mr. Akikusa ended up on the island of Iwo Jima. Through a translator, he described to us what it was like to watch the first Americans land on the island. In a small bunker near the beach, he saw the landing crafts approach, the marines unload and begin climbing the beach. There was no opposing fire. Quite anxious, he asked the officer next to him, “Why are we not firing?!” At that moment, the cannons erupted from the hidden bunkers and tore up the first Americans. Mr. Akikusa was relieved, but also horrified.

Throughout the rest of the battle, he remained on the island, but never fired a shot. As the end drew near, many of the Japanese soldiers in his bunker committed suicide. Then it was evident they would soon be overcome. He heard shouts and cries and saw the Japanese officers shooting the soldiers who were crying in fear. Afraid that they would shoot him, he didn’t say anything. Soon, his bunker was hit, knocking him unconscious. A few days, later he woke up in an American hospital tent. He learned that one of the War Dogs had sniffed him out during a patrol. When the Marine accompanying the dog saw that he was still alive, he brought him back for medical attention. Mr. Akikusa was one of only 1,000 Japanese to be taken prisoner on the island of Iwo Jima. Over 22,000 Japanese soldiers had been killed or committed suicide.

Mr. Akikusa spent the next year as a prisoner of war. Fearing his survival would cause shame for his family (who thought he was killed on the island), he never wrote home to tell them he was alive. It was one of the moral codes of their culture to die an honorable death in battle rather than suffer the disgrace of surviving, or worse -become a prisoner of war (This is one of the reasons the Japanese treated our POWs so poorly; they considered them to be disgraced men for surrendering). Eventually, after the war ended, he decided to go home. He arrived just in time to discover his school was having a funeral service for him and the other boys in his town who died during the war. He went quietly in, removed the picture of himself and sat down to attend the rest of the funeral. His funeral.

- - - - - - -

Mr. Akikusa attended the official ceremonies with us -the Americans. I’d seen him earlier in the hotel lobby. He was wearing a hat with GoArmy and USA pins on it. Knowing he was Japanese, but not having met him yet, I wondered how he came to be wearing a hat with American insignia. After hearing him relate his story, I knew. He concluded his comments by saying, “They say I was captured by the Americans. But I don’t like to say that. I wasn’t captured. I was rescued.”

Mr. Akikusa is an example of a man who once was our enemy, but now he is a friend. Some of the veterans on the trip were unsure about meeting someone they would have considered a bitter enemy. But putting aside enmity and deciding to forgive, they were able to shake his hand and welcome him as a friend. In response, Mr. Akikusa appreciates and respects our country for “rescuing” him.

After the ceremony, I saw that he was sitting alone with his translator. Walking up to him, I took his hand and told him how grateful I was for the peace between our countries and thanked him for coming with us - his former enemies - back to Iwo Jima to remember our fallen soldiers. He smiled so kindly and replied similarly. Pulling out my Polaroid, I asked to take a picture with him. If you remember Polaroids, they print instantly, so a moment later, I gave him one of the prints. He smiled when he saw the photo, and his translator explained to him that it was a gift from me for him. With almost tears in his eyes and holding tight to the picture, he thanked me.

It was brief, but the interchange meant a great deal to me. My great-great uncle died in a POW camp in the Philippines. His sister was very bitter against the Japanese for the rest of her life. I have known many people who experienced great hardships at the hands of the Japanese in WWII. But at the end of the day, forgiveness is one of the greatest acts a man can offer another. “Let all bitterness, and wrath, and anger... be put away from you...forgiving one another, even as God for Christ’s sake has forgiven you.” Ephesians 4:31-32

- - - - - - -

Following the ceremony, several of us piled into the back of a jeep and headed down to the beach. Getting to the sand was entirely different from anything I had imagined. You read about the difficulty the Marines had climbing the sandy embankments: move forward three feet, sink backwards and in two. It was impossible to dig foxholes for protection because of the texture of the gravelly sand which caved in and cut up the skin. It was all this and more.

My cowboy boots sank up to the top and sand poured in. Walking in them was like wearing moon shoes as I tried to walk. Because of time constraints, we didn’t go too far out onto the beach, but I heard later that some of the folks tried “storming the beaches” again, and found the task of scaling the inclines tremendous. (Side note: up to 10 months later, I was still finding sand from Iwo Jima in my boots, despite cleaning them and wearing them regularly)

I mentioned that the sand was rough enough to cut skin. Hard to believe, but true. Coming up from the beach, I tripped and cut my knee. The cut was small, but 13 months later, I still have the scars from it. With such a small incident leaving such a permanent reminder, I couldn’t help but think about the poor fellows who crashed into the sand for protection or fell wounded. I’ve been calling it sand, but really it is volcanic ash; the same hard, rough, gravelly volcanic ash that greeted the Marines on Iwo 71 years ago.

With evening coming, we headed back to the airstrip to fly back to Guam. We boarded our plane all in tact, carrying several additional pounds of black Iwo Jima sand. This sand was so popular that for a few minutes there was question if some poor soul would have to dump their portion to lighten the load of the plane. There were no volunteers and in the end everything was fine. Our flight back was uneventful (though two of the other planes ended up being grounded for a couple of hours before returning... Another story), and we chatted with the veterans and folks on the plane. Our trip was coming to a close.

The next day was the last day of the tour, finishing up with the closing banquet at the Pacific War Museum, a fabulous museum in Guam that boasts excellent artifacts and tremendous military equipment (jeeps, trucks, guns) scattered around the grounds. Nothing like enjoying your dinner at the base of a WWII anti-aircraft gun.

This may seem like the longest article I’ve ever written. Probably is. Unfortunately, as long as it is (and if you have persevered through it thus far, bravo and thank you), only highlights were mentioned. So much happened in such a short space of time that it is hard to put it all down and get it out the door. But for now, here are a few lessons I learned from Iwo Jima.

There is no underestimating the power of forgiveness:

On this trip, I met veterans who had carried great animosity and hatred toward the Japanese for the past 70 years. Understanding that what the Marines on Iwo Jima experienced is beyond our comprehension, it is still hard to see men in their 90s continue to carry bitterness against their enemy when their time left on earth is so short, because bitterness eats at the soul like nothing else. But, even the most angry man can overcome and forgive. I saw that happen.

The Brotherhood of the Marines:

It is rare you find a bonded brotherhood like the Marines. What makes a 90+ year old man make an incredibly arduous trip across the world to a barren and desolate island? Especially one that holds only the most painful of memories? Because he feels it is his duty to go back and pay his last respects to the comrades and friends he lost. Mr. Pontisso said about his wounds, “I don’t deserve the Purple Heart, it’s the ones who never made it back that do.”

He may have lost his arm 71 years ago, but to him, he came out with his life when so many others didn’t. He went back because it was important to him that he remember them and that others remember. The strength of the brotherhood was so strong that he and others were willing to put aside the personal pain of the memories and make one last return. One last Reunion of Honor.

We must never forget:

In an old war movie from the 1940s, White Cliffs of Dover, there is a scene at the end which always brings tears to my eyes. The young man, John, has been mortally wounded fighting in France during WWII. Lying in a hospital in England, he tells his mother about a conversation he had with another soldier. The interchange between the mother and her dying son pretty much sums up why we must never forget.

"That chap, the American, he said he'd really start to fight the day war ended: for a good peace, a peace that would stick. He didn't know he was going to die, you see. He said that God would never forgive us, either England or America, if we break the faith with our dead again. Write his mother a nice letter. Tell her that…,oh well, you'll think of something....”

A few moments later a parade comes by, and his mother looks out the window.

“How well they march, John... There is a look of greatness about them. All the strong young boys. Beautiful and proud with dreams. Just like you, John. They'll help bring peace again. And as your friend said, "A peace that will stick." …. You know, John, we must never forget what that American boy said to you. God will never forgive us if we break faith with our dead again.”

The memory of the boys who died on Iwo Jima, where “uncommon valor was a common virtue,” mustn’t be forgotten. Neither should the boys of Peleliu, Tarawa, Wake Island, Guadalcanal, Monte Cassino, El Alamein, Normandy, the Hurtgen forest, the Battle of the Bulge... None of them. If we forget, what was the point of their sacrifice?

I will never forget this trip to Iwo Jima. And I will make sure no one around me ever forgets either. If we are a grateful people, we will not forget the sacrifices of the men who died for our country. In Ernie Pyle’s book, Brave Men, he wrote, “I don’t believe one of us was afraid of the physical part of dying. That isn’t the way it is. The emotion is rather one of almost desperate reluctance to give up the future.”

So, thank you to all the young men who gave up their futures. The men who will be forever young in our memories. We may live to be 95, but they will always be 19 years old. God forbid that we ever break faith with them and, in our selfishness, forget the reasons we still live in a free country.